This post is also available in:

Español (Spanish)

Français (French)

Gastrointestinal Polyps

Polyps are tissue growths that extend out from the lining of the gastrointestinal system. They may occur in the stomach, small intestine, or large intestine (colon). Most commonly, polyps are found in the colon. To learn more about the symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment of polyps in children, download the GIKids Fact Sheet on Polyps.

What are polyps?

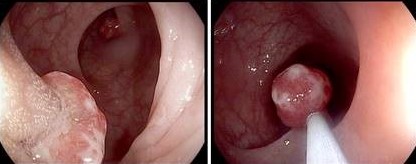

The lining of the gastrointestinal system is normally smooth, like the inside of your mouth. Tissue growing outward from the lining is referred to as a polyp.

Polyps may grow out of the lining of the small and/or large intestine or stomach. Most commonly, polyps are shaped like a mushroom, with a narrow stalk that connects a bulkier end to the intestinal lining. Other polyps are flatter and grow directly on the lining. The size of polyps may vary from less than one-tenth of an inch to more than one inch in diameter.

There are two general types of polyps: adenomatous and hamartomatous polyps. The type of polyp is based on what it looks like under a microscope. Adenomatous polyps are typically seen in adults and can put adults at risk of developing colon cancer. Hamartomatous polyps are the type of polyp usually found in children. Also called juvenile polyps, hamartomatous polyps are almost always benign, although patients with many hamartomatous polyps may be at increased risk of colon cancer.

How common are polyps?

A polyp may be found in the large intestine in about 1%–2% of children. The most common type of polyp is a juvenile polyp, accounting for more than 95% of polyps found in children. These are mostly found in children younger than 10 years old, and especially in children 2–6 years of age. Most juvenile polyps are solitary (a single polyp) and are found mostly in the left side of the colon.

Some children inherit genes that make them more likely to develop many polyps (referred to as polyposis syndromes). Some of these polyposis syndromes involve hamartomatous polyps, while others involve adenomatous polyps. Polyposis syndromes include familiar adenomatous polyposis, juvenile polyposis syndrome, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome, and Cowden disease. Unlike solitary juvenile polyps, polyposis syndromes may increase the risk of intestinal cancer. Polyposis syndromes are diagnosed with a combination of a thorough family history, endoscopy, microscopic examination of the removed polyp, and genetic testing.

What are the symptoms of polyps?

Children with polyps usually pass blood in their stool. This bleeding does not cause pain for the child. With small amounts of bleeding over months, some children can develop iron-deficiency anemia and may have symptoms of anemia (such as fatigue, pale skin). Bleeding may not happen with every bowel movement and tends to recur over weeks to months. It is rare for children to have other symptoms, but other symptoms can include: crampy abdominal pain, diarrhea with mucus, or even prolapse of the polyp. Prolapse is when the polyp partially sticks out of the anus, while still being attached to the wall of the large intestine.

How is the diagnosis made?

If a child has prolapse of a polyp (the polyp sticking out of the anus), the diagnosis is easy to make because the polyp can be seen by the parent or the doctor. More commonly, a child is referred to a pediatric gastroenterologist for passing blood out of the intestines (rectal bleeding).

Your doctor will recommend a colonoscopy, in which a narrow bendable tube mounted with a camera and a light are used to look directly into the large intestine. When a colonoscopy finds the source of the bleeding, the gastroenterologist uses a small grasping tool called a snare that fits inside the colonoscope to remove the polyp. The polyp is then sent to a pathologist, who will look at it under the microscope to determine what kind of polyp it is. The gastroenterologist will inspect the entire large intestine with the colonoscope to make sure there are no other polyps. Usually, all polyps are removed (unless there are very many or it is unsafe to do so).

A diagnosis of one of the above-mentioned polyposis syndromes may be made if the doctor finds certain clues during their examination. For some of these, special genetic tests can be performed with a blood test to confirm the diagnosis.

What are potential complications of polyps?

If a child has prolapse of a polyp (the polyp sticking out of the anus), the diagnosis is easy to make because the polyp can be seen by the parent or the doctor. More commonly, a child is referred to a pediatric gastroenterologist for passing blood out of the intestines (rectal bleeding).

Your doctor will recommend a colonoscopy, in which a narrow bendable tube mounted with a camera and a light are used to look directly into the large intestine. When a colonoscopy finds the source of the bleeding, the gastroenterologist uses a small grasping tool called a snare that fits inside the colonoscope to remove the polyp. The polyp is then sent to a pathologist, who will look at it under the microscope to determine what kind of polyp it is. The gastroenterologist will inspect the entire large intestine with the colonoscope to make sure there are no other polyps. Usually, all polyps are removed (unless there are very many or it is unsafe to do so).

A diagnosis of one of the above-mentioned polyposis syndromes may be made if the doctor finds certain clues during their examination. For some of these, special genetic tests can be performed with a blood test to confirm the diagnosis.

Author: Jubin Matthews, MD

Editor: Athos Bousvaros, MD

April 2021

This post is also available in:

Español (Spanish)

Français (French)