This post is also available in:

Español (Spanish)

Français (French)

What is rumination disorder?

Rumination disorder is when your child automatically regurgitates food and/or liquids, often very soon after eating or drinking (usually within 30–60 minutes). The regurgitated food and/or liquids are either re-swallowed or spit out. Rumination disorder can appear differently in different children.

How common is rumination disorder?

Research shows that 2%–3% of people have rumination disorder. However, rumination is likely more common because it often is not recognized or diagnosed. Rumination disorder is more common in some groups, including people with intellectual and developmental disabilities or eating disorders. Rumination also is frequently seen in pediatric gastroenterology clinics, where it can be difficult to distinguish from acid reflux and vomiting. The timing, volume, taste, and force of regurgitation all provide clues about whether it is rumination disorder.

How is rumination disorder diagnosed?

Rumination disorder is diagnosed using a list of symptoms called the Rome diagnostic criteria. To be diagnosed with rumination disorder, a child must have repeated regurgitation, rechewing, or spitting up of food that: 1) begins soon after a meal, 2) does not occur during or after sleep, 3) is not preceded by retching, and 4) is not explained by another medical condition including an eating disorder.

Why does rumination disorder occur?

Rumination symptoms may begin after an infection, stressful event, or gastrointestinal disease. However, many cases have no obvious trigger. Rumination syndrome also can occur in patients with other gastrointestinal conditions.

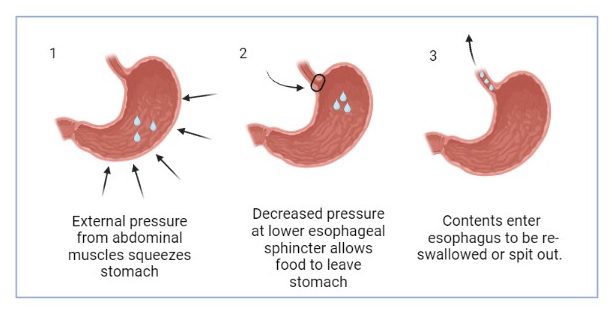

Rumination is thought to be caused by pressure placed on the stomach by involuntary squeezing of the abdominal muscles. This means that the child is not consciously squeezing their muscles. In addition, decreased strength of the muscle that separates the esophagus and stomach (called the lower esophageal sphincter) can allow stomach contents to flow back up to the mouth.

For most children, the regurgitation is thought to start as the body’s way of releasing uncomfortable pressure in the abdomen. It then becomes associated with a positive outcome, such as a pleasant food taste and/or less abdominal discomfort. This reinforces the behavior. Repeated over time, this loop can become a “habit” that continues even after the original trigger is no longer there.

Created with BioRender.com

How is rumination disorder treated?

Treatment of rumination disorder occurs with coordinated care between a psychologist and pediatric gastroenterologist. The best strategies may depend on the child age, how the child gets nutrition (such as eating by mouth, or have a feeding tube), the child’s stage of development, and whether the child has other gastrointestinal symptoms that may trigger rumination. When possible, treating the underlying trigger can help break the “habit” of rumination.

For normally developing children who are at least school-aged, a common rumination treatment is diaphragmatic breathing. This strategy teaches the child to breathe from the abdomen and diaphragm instead of the chest. This treatment can help overcome the automatic muscle contraction and improve strength of the involved muscles. A psychologist or therapist can help a child learn and practice this breathing technique.

Some children can benefit from other treatment methods. Habit reversal treatment involves three main components: 1) increasing awareness of the urge to ruminate, 2) using a competing behavior to prevent or stop rumination, and 3) relaxation training. Some competing behaviors might be chewing gum or sucking on hard candy after meals. These competing behaviors involve repeated swallowing, which can interfere with the flow of stomach contents up the esophagus. Both strategies can help retrain the stomach to get used to normal pressure in the stomach until food begins to be digested (usually within 30–60 minutes after meals).

Consistently stopping regurgitation using deep breathing or another competing response, avoiding trigger foods, having good posture while eating, and re-swallowing the regurgitated contents when breakthrough occurs are also keys to effective treatment. Medications may be considered under the direction of your child’s care providers and may involve protecting the esophagus, decreasing the feeling of pressure in the abdomen, and/or addressing any underlying trigger.

For patients with developmental concerns or very young children, it can be difficult to teach diaphragmatic breathing to manage rumination. Further, they may be less aware of the urge to ruminate. Changing behaviors to reduce rumination may be needed based on the child’s developmental level, ability to chew gum or suck on candy safely, and their other medical conditions. Other potential strategies include brushing teeth after eating a meal or giving the child a sour or spicy food/liquid after rumination. However, these strategies should only be tried after talking to your child’s care providers.

Can rumination disorder come back?

Relapses or flares can occur, and retreatment may be needed. Similar to all diseases, stress, poor sleep, illness, or other physiologic triggers may contribute to recurrence of rumination disorder. However, once the skills to manage rumination are learned, they can be reused if symptoms come back.

What are some good resources for learning more about or managing rumination disorder?

Josefsson A, Hreinsson JP, Simren M, et al. Global Prevalence and Impact of Rumination Syndrome. Gastroenterology. Mar 2022;162(3):731-742 e9. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2021.11.008

Martinez M, Rathod S, Friesen HJ, Rosen JM, Friesen CA, Schurman JV. Rumination Syndrome in Children and Adolescents: A Mini Review. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:709326. doi:10.3389/fped.2021.709326

The Rome Foundation. Rome IV Criteria. 2016. https://theromefoundation.org/rome-iv/rome-iv-criteria/

Authors: Jennifer Schurman, PhD, ABPP, BCB; Price Edwards, MD; Christina Low Kapalu, PhD

Editor: Amanda Deacy, PhD

October 2023

This post is also available in:

Español (Spanish)

Français (French)